During the '70s there were 1,000 Minuteman ICBM missile silos in the

U.S. The name 'Minuteman' was chosen because they could launch in

as little a a minute after the launch command was input. At that time I

was stationed at Whiteman Air Force Base, Knob Noster, Missouri, as an

ICBM Minuteman II Flight Commander. The following photos are of a

typical Launch Control Center (LCC) located at Whiteman.

There were three missile squadrons at Whiteman, the 508th Strategic

Missile Squadron, the 509th Strategic Missile Squadron, and the 510th

Strategic Missile Squadron. Each squadron had control

responsibility for 50 ICBM missiles with atomic warheads. Each

missile squadron contained five LCCs with prime responsibility for ten

missiles each. The LCCs and the missiles were spread over a wide

area of the Missouri countryside and some missile crews had to drive as

far as ninety miles to their LCC. Whiteman is now a B2 stealth

bomber base and all missile sites have been deactivated. However,

there is still one LCC open for visitors, Oscar LLC, located on the

base itself.

At ground level above each LLC was a Launch Control

Support Building (LCSB)with military police on duty. The LCCS

were located underground and were accessed by an elevator in the

LCSB. At the bottom of the elevator was a Launch Control

Equipment Building (LCEB) containing an emergency diesel generator as

well as food supplies and various other items. The Launch Control

Center (LLC) was a separate structure shaped like a medicine capsule

and constructed of reinforced concrete with a entry blast door

approximately three feet thick. The LCCS were

designed to withstand anything other than a direct hit by a nuclear

weapon.

Of the 1000 Minuteman missiles, six were ERCS

(Emergency Rocket Communication System) missiles. Rather than

warheads, these ERCS missiles were topped with radio

transmitters. In case of war, ERCS crews on duty would record the

go-to-war message from SAC (Strategic Air Command) headquarters onto

two ERCS missiles which were then launched east over the Atlantic and

west over the Pacific. During an atomic war, many forms of

communication would likely be interrupted. The ERCS missiles were

intended to ensure that our ships at sea, especially submarines armed

with nuclear missile, received the launch message in a timely

manner. In 1971, my deputy, 2nd Lieutenant Jerry Vanlear, and I

launched one such ICBM at Vandenberg AFB,California. I recorded a test

message and then launched the ICBM out over the Pacific. A minute

or so later we heard my voice over the launch center radio transmitting

the message I had recorded.

If a launch command were given by SAC Headquarters

as directed by the president, the crews on duty would verify the

message by removing their locks from the small safe in the LCC and then

breaking open the coded verification documents in the safe. They would

also removing the two launch keys in the safe. The crews in each

squadron would conference by phone and initiate the launch

process. Depending on the contents of the launch message, crews

would enter targeting information into their computers. The launch keys

would be inserted and at the proper time all crew members in the

squadron would turn keys simultaneously. In an actual war, one or

more of the LCCs might be destroyed before launch time, thus the system

only required a minimum of two LCCs to start the launch process.

If the LCCs had been destroyed by incoming warheads all ICBMS in the

squadron could still by launched by personnel on SAC aircraft that were

flying twenty-fours hours each day for that purpose.

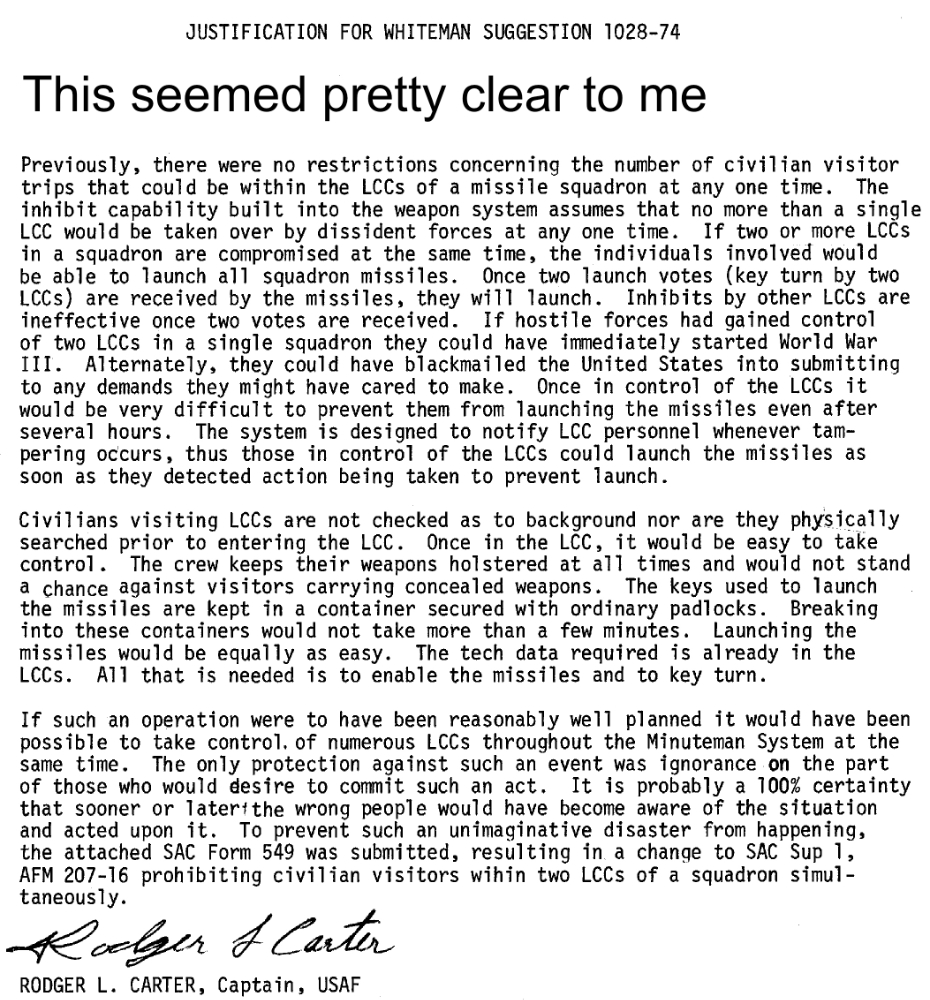

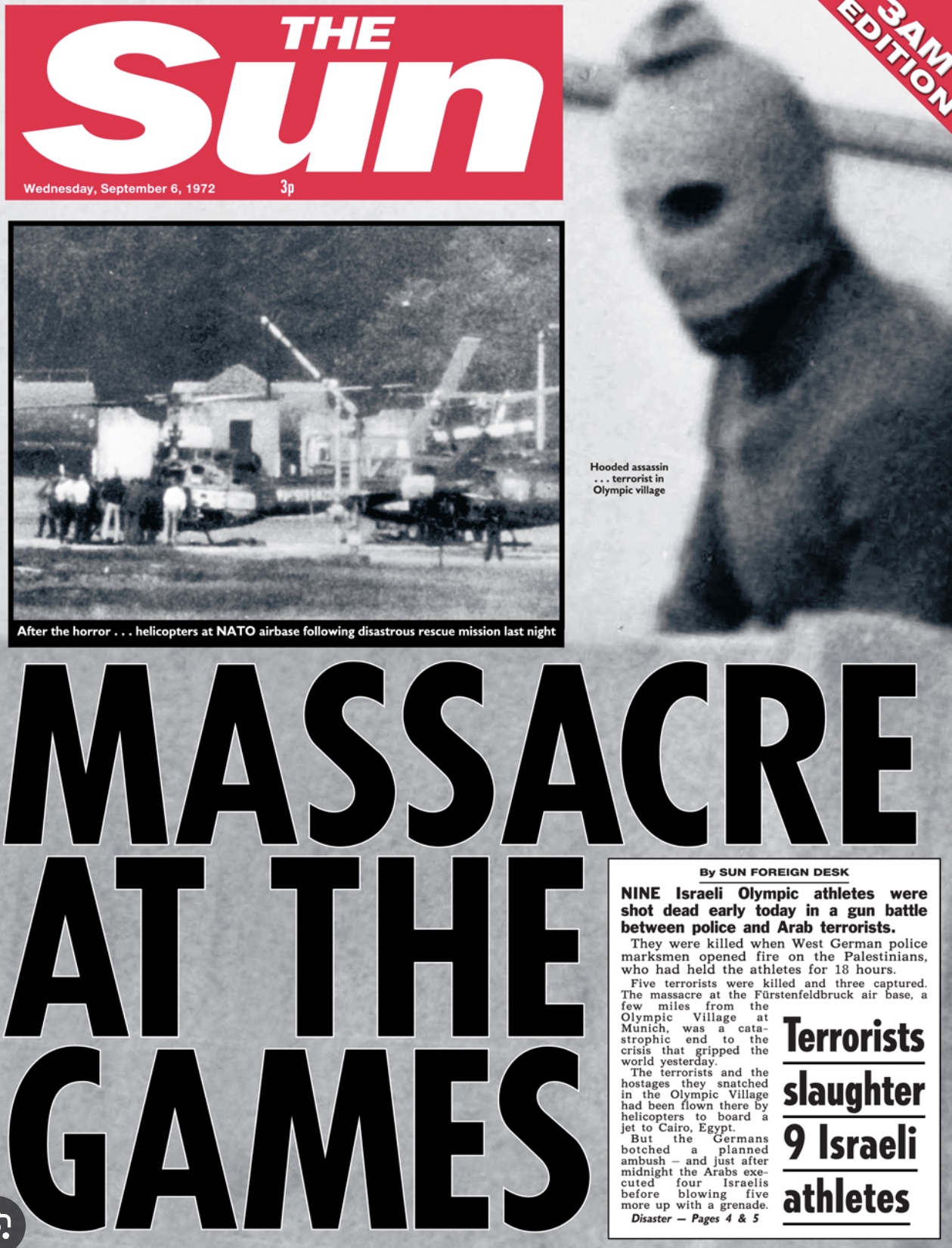

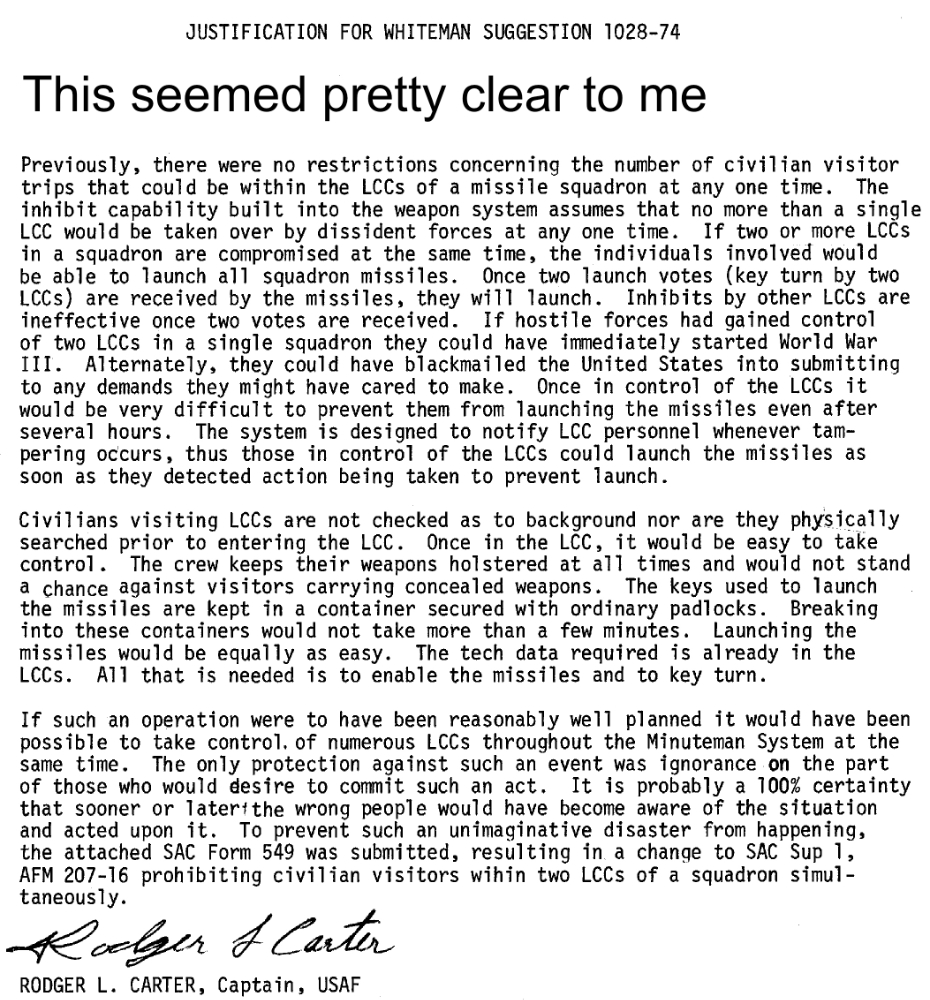

At the time I was assigned to missile duty at

Whiteman AFB, it was the custom to allow individuals or groups to

visit any LCC or LCCs in a missile wing. Visitors were not

searched nor subject to any security measures other than having to

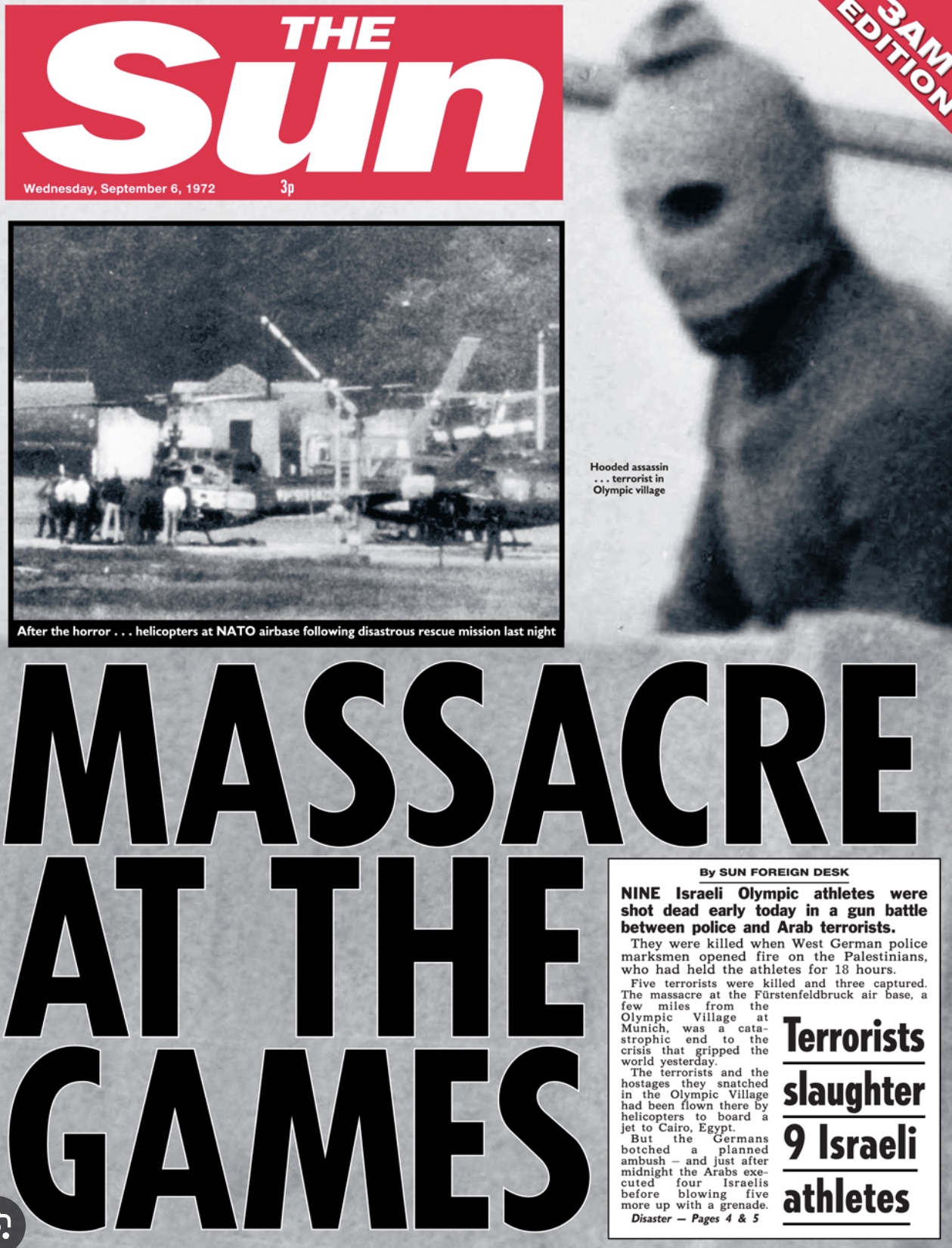

obtain a trip number prior to visiting the LCCs. This was during

the time period when terrorists had killed many Israeli athletes during

the 1972 Olympics. I discussed the visitor procedures with

my squadron commander, pointing out that it only took launch commands

from two of the five LLCs in a squadron to launch that squadron's

missiles, and that it would be quite easy for terrorists to conduct

visits to two LCCs in a squadron and then take over the LCCs and launch

50 nuclear missiles resulting in a nuclear war. In fact, it had

been nothing but sheer dumb luck that such an event had not already

taken place. My commander agreed and asked my to inform

Headquarters Strategic Air Command (SAC) of the situation. I

spoke to a colonel at SAC who became quite excited when I informed him

of how easy it would be to put the U.S. in such an untenable

situation. He said he would call me back on the matter and he did

so several hours later. He no longer seemed excited or upset at

the possible prospect of an imminent nuclear war and asked me to submit

an emergency classified change to the regulation limiting visitor trips

to no more than one LCC in a squadron at any one time throughout SAC,

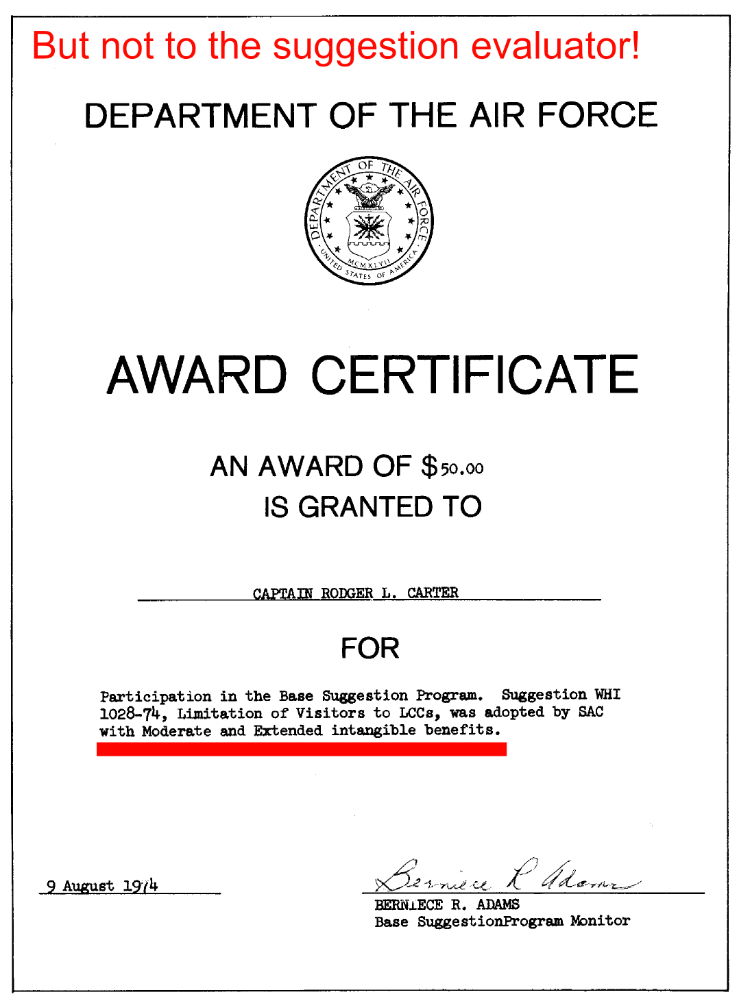

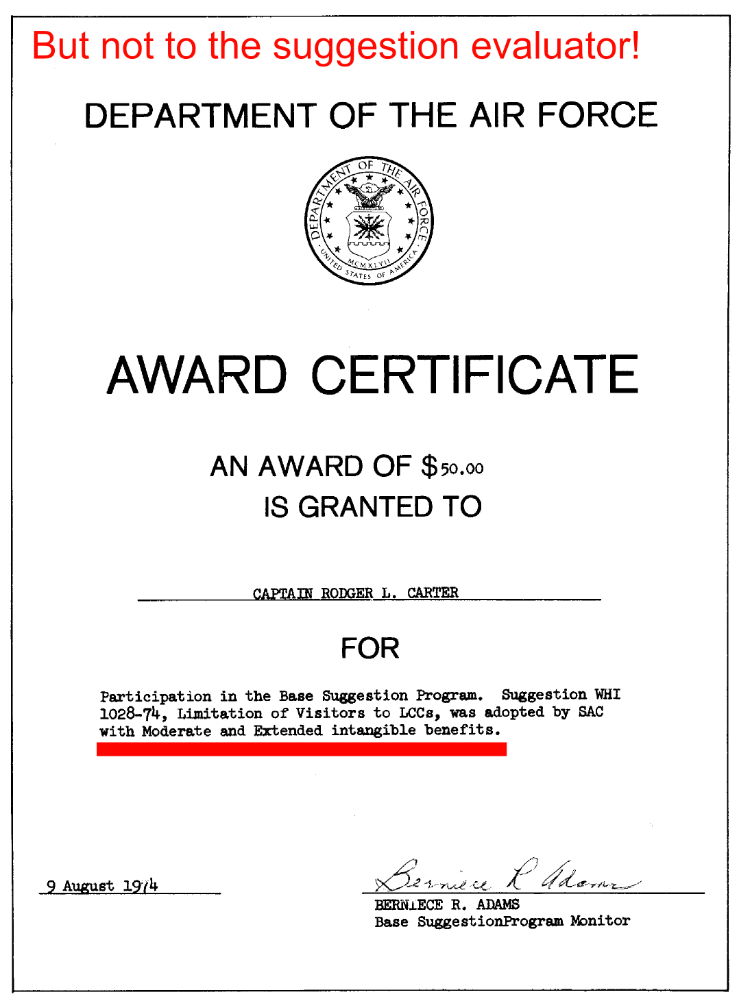

which I did. After the regulation change was made, I submitted an

after-the-fact suggestion through the base suggestion program outlining

the extreme danger we had been in and that it was only by great good

luck that the wrong persons had not become aware of the situation and

taken advantage of it. Sometime later I received notice that the

suggestion had been adopted by SAC and I was given an award of ----

$50. The award letter stated that the suggestion had provided

"moderate and extended benefits." I spoke to the little old lady

in tennis shoes in the suggestion office at SAC who had approved the

award and she told that it was worth no more than $50 because it only

affected six SAC bases!

Several years later I happened to be working in the

same organization with an officer who had been at SAC Headquarters when

my call was received. He told me that the apparent calm of the

colonel who had called me back was just that, apparent. He said

that my call had turned SAC headquarters upside down and that they were

frantic to devise a method whereby the possibility of such a

catastrophic event taking place could be positively eliminated.

Merely depending on bases strictly adhering to the changed LCC visitor

regulation would not be sufficient. Changes were made to

procedures and LCC equipment whereby the crew would receive coded

information in a launch message which had then to be inserted into LCC

equipment before the missiles would respond to launch commands.

That change absolutely prevented unauthorized launch of missiles by

anyone, including LCC crews.

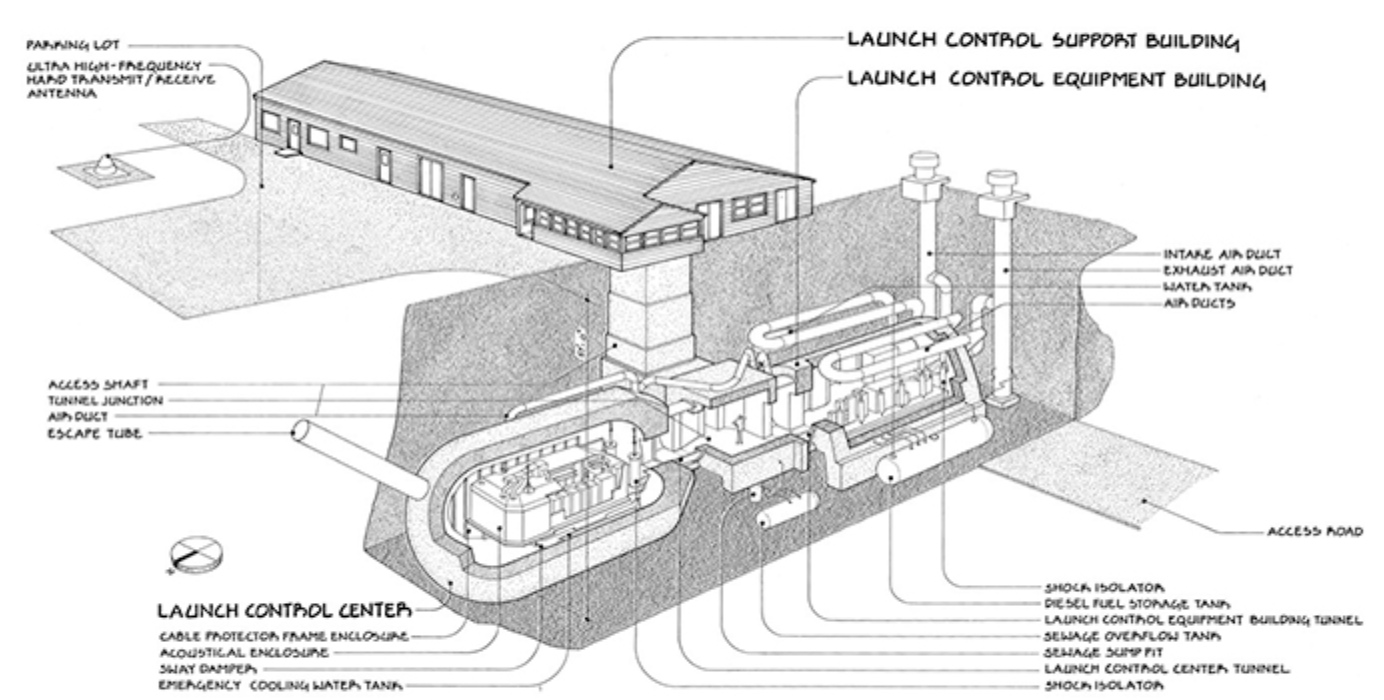

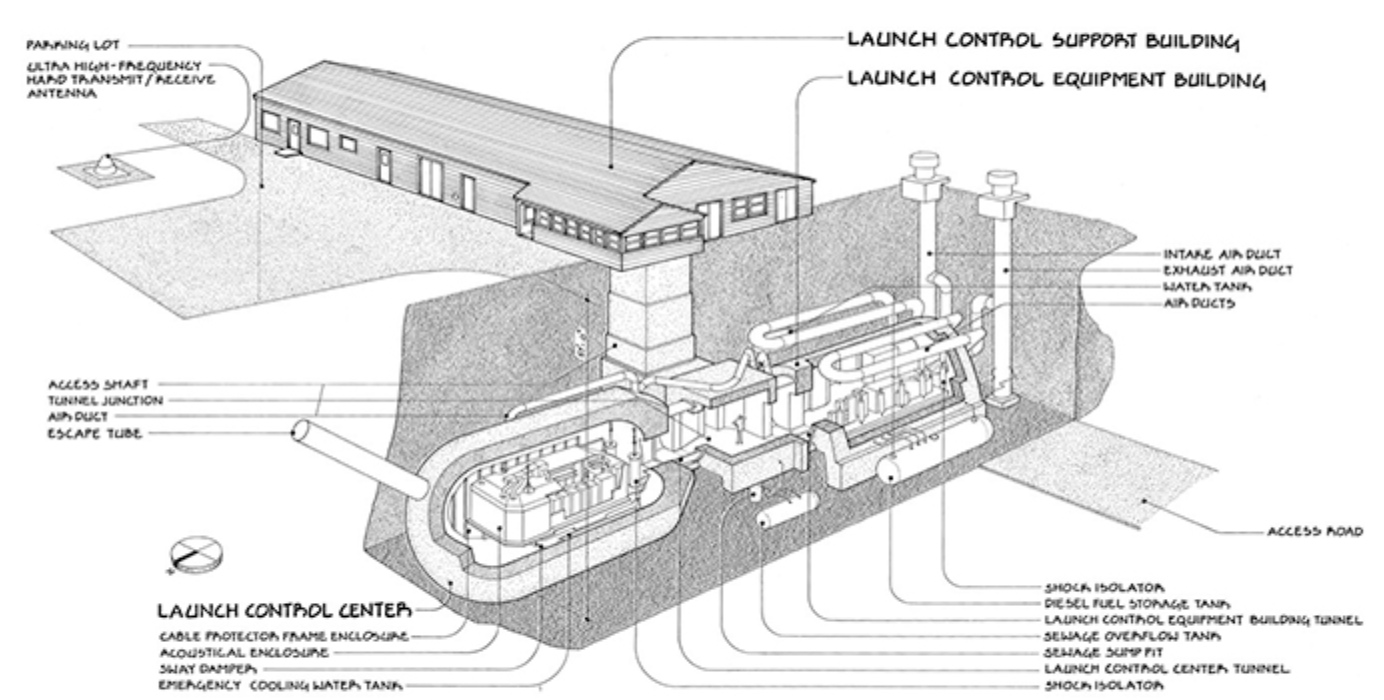

Above is a diagram of a typical Launch Control Facility. All

personnel enter through the building shown in the upper center. Crew

members would go down the elevator shaft shown in the center of

the diagram to the LCC. On the lower right is shown the Launch

Control Equipment Building (LCEB) which contained an emergency

generator, food supplies, and other miscellaneous items. The LCC

is shown in the lower center of the diagram and was shaped like a

medicine capsule.

Blast door entrance to the Launch Control Equipment

Building. Inside

the LCEB

Emergency generator.

Launch Control Center blast door. It would take the bad guys quite a while to work their way through that door.

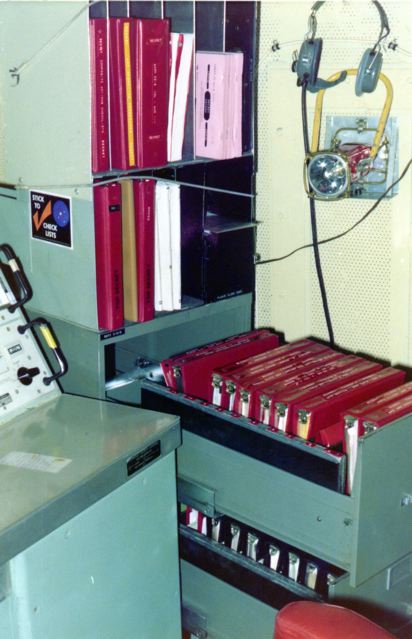

LCC Commander'swork station

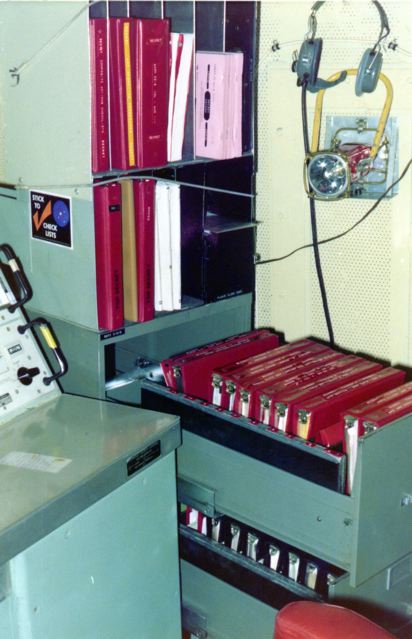

Manuals

and

Regulations

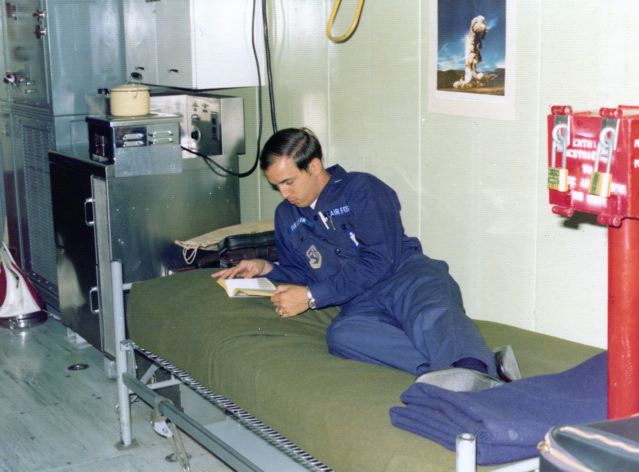

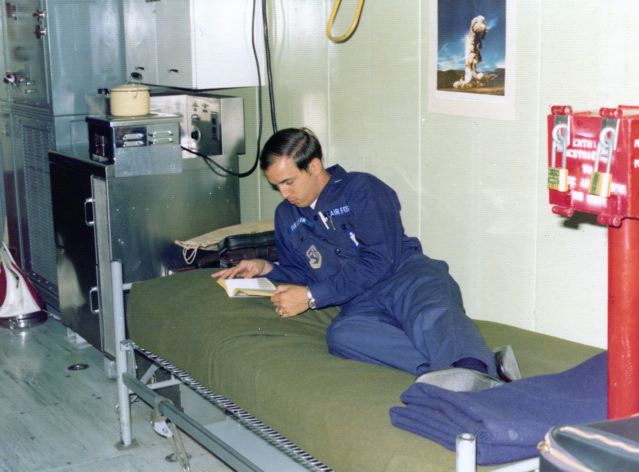

Deputy Work Station

Deputy LCC Crew Commander pursuing intellectual studies (maybe).

The photo on the left is of what was unaffectionately known as the knee

knocker. It was used to record a copy of the go to war

message on six ERCS (Emergency Rocket Communication System) missiles

located only in the 510th Strategic

Missile Squadron at Whiteman AFB. Those six missiles did not have

atomic warheads, but instead radio transmitters used to broadcast the

war message out over the western U.S. and the Pacific Ocean, and

eastward out over the Atlantic Ocean. Such transmissions might be

especially important to submarines and ships because nuclear blasts can

disrupt normal communications. I and my deputy, Lt. Jerry

VanLear, Launched an ERCS missile from Vandenberg AFB in

March of 1972. It worked fine, the message I had recorded

on the knee knocker began broadcasting a minute or so after launch.

The photo on the right is the safe

where the launch keys were kept as well as the documents used to

authenticate a launch message.

This last piece of equipment is highly classified, so I am not allowed

to describe its function to you, but be sure it was very

imporatant to the war effort (and some other efforts too).